La Vie Migrée

A blog about my migration experience, by Thura Nu

(28/5/2021)

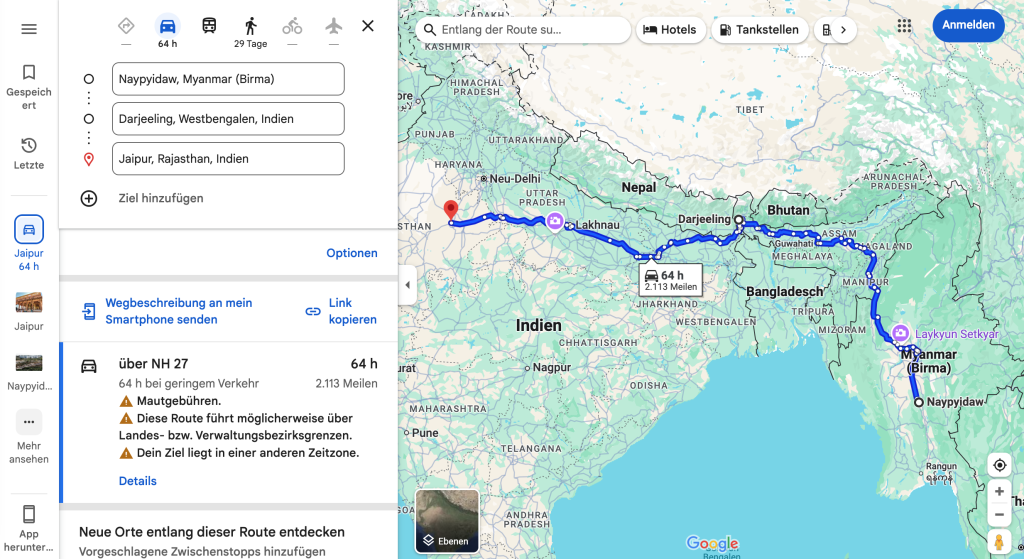

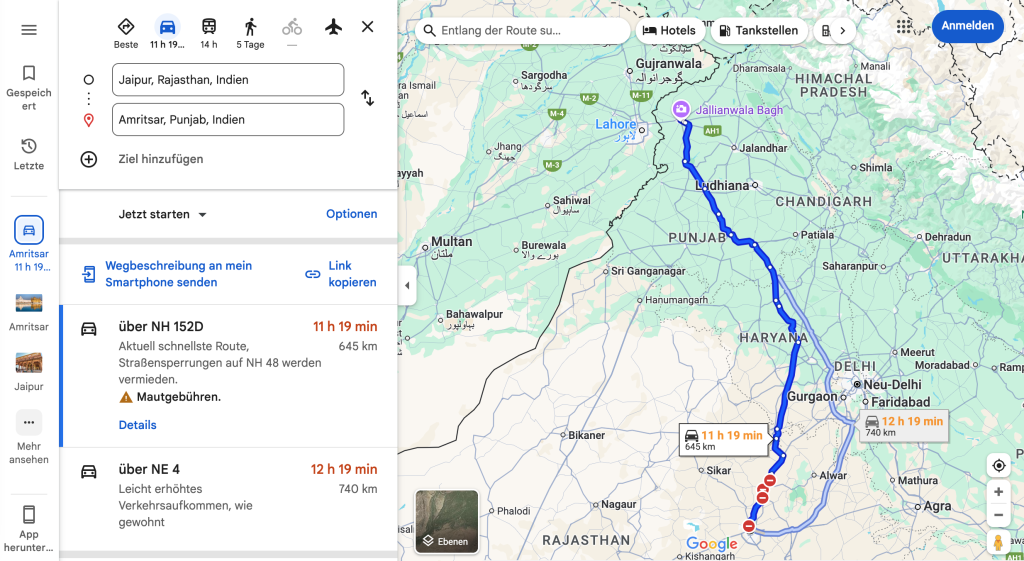

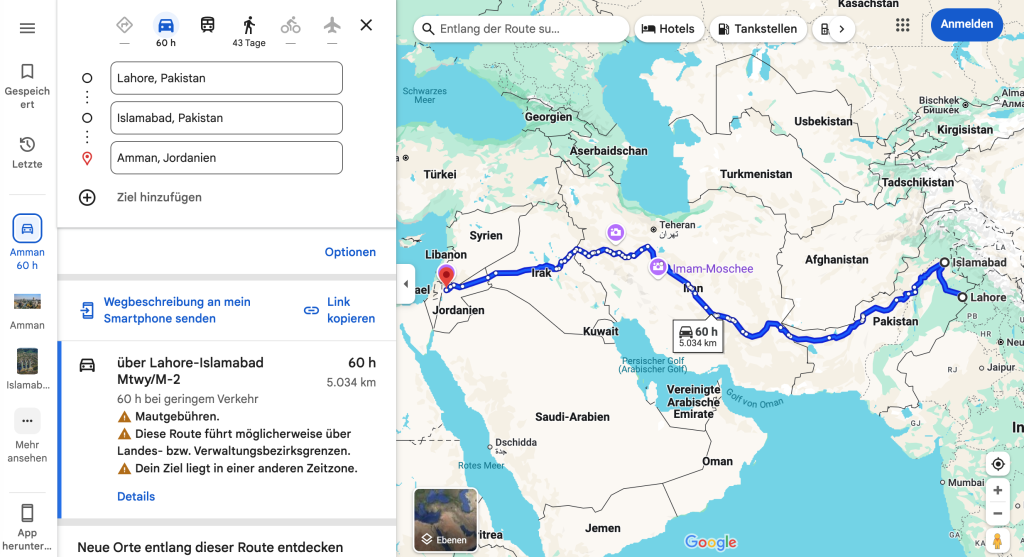

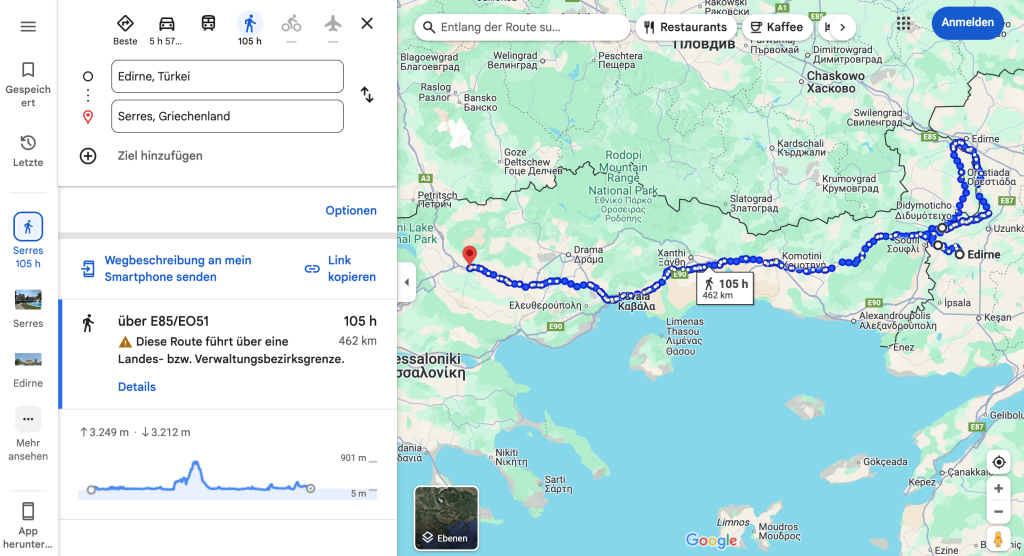

My name is Thura Nu (သူရ နု), I am a 35 year old man from Yangon, a small city in Myanmar, and I am a migrant in need. Thura which is a kind of epithet, means “bravery, courage, resilience;” I have found this to be a useful epithet to carry with me in these past weeks. As of my writing this, I have officially been denied from my asylum application in Germany, as they deemed my reasons unfit for asylum, labeling me as a so-called “economic migrant” rather than someone escaping an active civil war, only because I left before the war broke out. When the coup-d’état took place in early February, I knew I needed to escape. It was an idea I had already floated around for some time, since before the new year (in the Burmese calendar, so in the Gregorian calendar around March 28th). The tensions have already been in place for quite a long time, and amongst my friends we all would talk about how it was only a matter of time before it all boiled over. There was talk of protest and bringing down the military dictatorship, and I did not want to be involved in that; so I left for Europe. I had received a French education from the French School in Yangon, so unlike many of my compatriots at the “college de la photographie” who headed off to Shanghai, Guangzhou, Saigon and Singapore, I felt that I would have the best chance in Paris. Though in Myanmar I was quite affluent, I was still unable to afford a flight, so the next best option was to take a bus. Despite the long and arduous journey that lay ahead of me, in late April, 2021, I boarded a bus in Naypyidaw that took me North from the heart of Myanmar, up to the North Eastern part of India that straddles Bangladesh, a region I learned is called locally the “seven sisters,” for being comprised of seven states (and an eighth, that is referred to as “the brother”). From here, changing in Darjeeling, I continued my journey westward, reaching Jaipur in western Rajasthan in several days. After convincing a convoy traveling over the border with Pakistan to take me with them, saying that I was a traveling war photographer (at this time I still had my camera from back home) who wanted to document the border. Once inside Pakistan, I made my way to Islamabad, from where I was able to join another convoy, this one headed farther west, for Jordan.

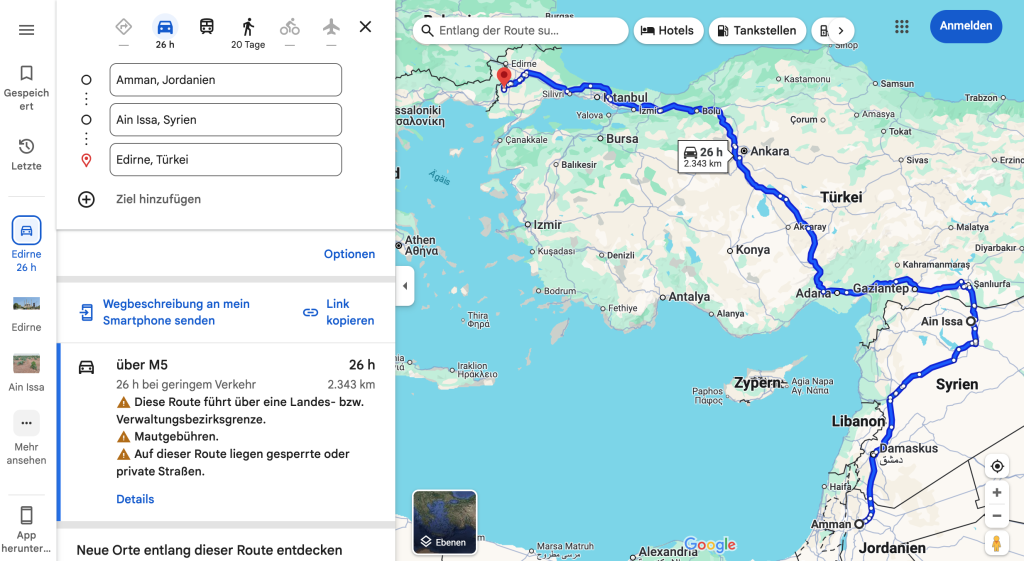

By this time, it was now May (my month of Kason) and word reached me that indeed a civil war had broken out. I thought of my family, who had considered leaving as well, but had been unable to decide on a destination. My brother was quite affluent, so I had no doubt that he would find a way to get them safely to a neighboring country in a time of need such as this. But, truth be told, since I became an adult I have not been so close to my family. It took another four six days of bus riding and border passing and checkpoint crossing to reach Amman, the capital of Jordan. In my brief research about migrations to Europe, I had read that Jordan had become a kind of stepping stone, and my thinking was that I could go from there on to Europe, the land of golden opportunities, fairness, justice, due process, and humanitarianism, where surely they would see my merit and accept me in as a migrant… or so I had been told by my schooling. But, as I would soon find out, I was mistaken. After managing to get into a refugee camp in Jordan, I was finally in a position to move northward towards Turkey and cross into Greece, having heard too many horror stories of crossings via boat. It was difficult to find a group that was willing to make the journey, but there were enough of us, and some kind souls in the Kurdish militia that held the north of Syria said they could arrange for us to cross safely into Turkey, so we trusted them. When we made it to the north, they did indeed get us across the border, but not without stripping us of all our possessions. That was when I lost my camera, my papers, and my passport; but I still believed that I would have a chance in Europe.

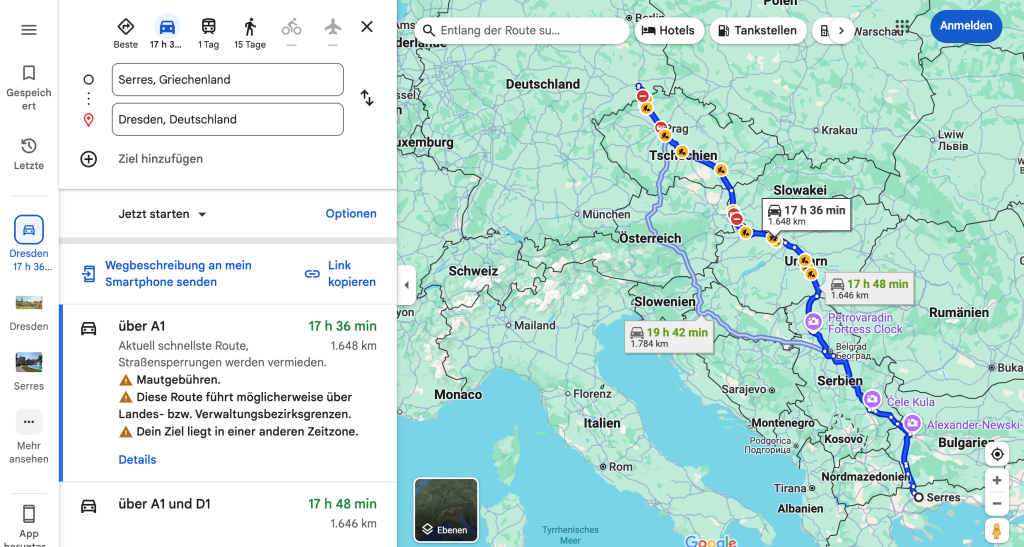

By a miracle I was able to cross Turkey relatively undisturbed, and a small trail through an unguarded region of brushlands in Thrace assisted my night passage. Once in Greece, I was able to join a northward trek towards Germany. Once we arrived, I decided to apply for asylum there, as they are known to accept many applicants and to welcome many migrants. But for the first time in my journey, they seemed unable to look upon me with pity, only they saw me as a number on a sheet, an item to be checked against a list. Where did you come from? And why don’t you have a passport? And what were you escaping? And when did you leave? All of these questions provided insufficient answers, and I was unable to supplement with any details that went un-requested. As a result of their insistence to not listen to my full story, I was denied asylum by the government of Germany, and told to perhaps try somewhere else. So I am headed to Paris now, and I have reverted back to my original plan of trusting the indomitable humanitarianism of the French; I am starting this blog to officially document my journey in detail, so that when I arrive in France I may be treated with the same dignity that is supposed to any decent citizen who still holds their passport, which is after all just a record of one’s travels. I only need access to a computer, like at this public library, here in Dresden.

– Thura Nu

(13/8/2021)

I have finally been given access to the computers here at the Maison. It has been several months since I was able to write to this website, and in the mean time much has happened. I have learned just how different Europe is than the image of it I was taught back in Yangon. I arrived at Bercy station around midnight on the 14th of July (2nd of Wahgaung), and under the “cover” of a stark lack of police, as they were all stationed at the Champs d’Élysée, guarding the new crowds that had finally been allowed to form and celebrate after more than a year of lockdown. I was able to accompany a small group of migrants who were on the same bus as me to a camp in the Jardins d’Éole in the XVIIIème. The experience of a migrant camp in Paris is far different from that of the ones I passed through in Jordan, Germany, and Pakistan. Back there, there were two demographics: the refugees, and the guards. The guards were there to keep the peace, but also to ensure that the processing of migrants went smoothly; but here it was only migrants. The police would stand at the edge of the garden with their big military-grade assault rifles, staring us down, waiting for one of us to do something so they could storm in and clear the place out. When I arrived, I quickly learned that the once beautiful Jardins d’Éole had become an epicenter for the current crack epidemic that was affecting the people living in Paris’ streets, and the police were just waiting like dogs on the edge of the fence for someone to make the wrong move so they could come in and clear us all out. And sure enough, on the 19th of July, the camp was cleared out and I was taken into police custody. Sitting in this jail cell in the préfécture, I began to wonder why I had even decided to leave Myanmar in the first place. The journey had been long and difficult, but I had done it all under the guise of being treated as a person in need of help when I arrived in Europe, the supposed “land of humanitarianism.” But upon my arrival, I had been doubted, duped, lead astray, and finally forced into the rough hands of armor-clad police who seemed only to care about meeting a quota of brutality before the night was over. One of the men who came with me from Bercy, Ahmann Jean-Pierre Aziza, had disappeared under the wave of policemen who arrived under the light of the moon. The last I saw of him, his neck was being squeezed to the grass by a knee, covered in a thick, plastic shell. I myself can still feel the spots where the metal screws on the plastic elbow-pads pressed into my skin as I was hauled into the back of a truck, along with fifteen-or-so other migrants who, like me, had never done crack a day in their lives, they had only been people in need of a home, and Jardins d’Éole had offered it to them; something that the rest of Paris was determined not to do, it seemed. They pressed me with questions, but it seemed wise for me not to answer directly. I simply said I was not supposed to be there, and I had been caught up in the rush, but I was beginning to lose faith. However, seemingly via some internal error, I was released, as though my French was anything but native they assumed me to be a homeless vagrant, and since I had no crack in my system, let alone drugs or alcohol of any kind, they let me off on a stern warning. In retrospect, it was smart not to tell the police my story, as I am not sure I would have ever made it out if I had. After two days in the jail, I was back on the streets. While in police custody, I had heard some of the offiers on the phone with an organization called “OFII,” the French Office of Immigration and Integration, a government agency that was determined to help migrants of any status with remaining in France and being integrated into French society at large. That seemed to me to be this “humanitarianism” I had heard so much about, and the spark of hope was reunited. On Monday the 21st of July, I walked into the offices of OFII at Porte de Clingancourt, and asked if they could help me apply for asylum, as I had been previously refused in Germany on account of a lack of such institutions there. They informed me that since I had been denied in a previous EU country recently, that I would have to wait a total of 18 months before attempting to apply again. But, they told me that they could get me a warm place to stay in the meantime, and they were able to find me room and board in the Maison des Réfugiés in the XIXème. I have a small room that I share with three other refugees. It is nice, I have learned a lot about these people’s stories. One young man, coming from Afghanistan, had the same problem as me. Denied in Germany for lack of a “good enough story,” he has been forced to wait for 18 months until he can apply again. As if somehow the humanitarianism that we were afforded was on a cool-down timer and had to be reset or tinkered with so that next time it could be just right.

-Thura Nu

(4/12/2021)

Today I was at the Marché aux Pouces in the nearby Saint-Ouen area, and I approached a camera seller who had a collection of cameras that caught my eye. We spoke for a while about cameras, and he asked me where I had come from. I told him my story, and he listened, intently, for several minutes. I had become accustomed to running through the narrative in my head, and telling it to people at the Maison, who in turn had stories just as arduous to tell: it had become sort of innocuous. It was still a hefty story to tell, but I told it with such ease one might have thought I made it up right then and there on the spot, or that perhaps it had happened to me in my youth. But the camera salesman looked at me, and he said to me: “I take pity on you my friend, never have I met a man with such an arduous journey.” He then handed me a camera, as I had told him of my previous job as a photographer, and he said he was giving it to me as a second chance. I feel incredibly touched. Since I arrived, people have been both good and bad to me, but no one until this man has had such compassion as to say these words to me, “I want to give you a second chance.” It has always been about my first chance, that somehow I am still in the process of arriving there at it; but he saw how I had journeyed, he saw what I had done to get here, and he saw something that I am not sure I had even seen up until this morning. That, truly, I had been given a chance, and that it was taken from me.

I felt it would be too much to ask the man for a photo, though I regret the decision now; but I was able to get this photo during my walk back to the Maison. I think that this face looks a bit like that kind man, standing guard ambivalently above the entrance to my second chance.

-Thura Nu

(28/3/2022)

I write to the website now from a phone I have managed to get my hands on while using the starbucks wifi. I have lost my standing at the Maison, and I am now out on the streets again. Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, the center has been flooded with new migrants from Europe, and though I am sure nobody would like to admit it, the system is all but outright preferential to them, choosing to oust residents who have done any small misgiving in favor of a more pallid migrant in need of a home. I, for my part, had nothing to do with the affair other than protecting my own property. A new bunkmate had recently moved into the room, and once he saw that I had a camera, he thought that he could just steal it from me to pawn it off, no doubt at the same market that I had acquired it at. But only because I chose to defend my right to my property, I was kicked out to the curb for disturbing an already stringent peace. They did however allow me to camp out in the “overflow zone” in the park outside; but in the biting cold I decided to try and seek warmth elsewhere, as the zone, which had once been marked for a capacity of 50 people, was now home to at least 300. In the biting cold of March, I have found the best place to sleep is on top of one of the metal grates that is always spitting out warm air. If I put my blanket, which I managed to stuff into a small bag before leaving, over the edges of the lattice, I can trap the hot air underneath it for a small period of time and preserve my warmth even more. Here are some of the places I have elected to sleep when the grates are occupied or I become too comfortable and the fear of being arrested seeps back into my bones.

-Thura Nu

(14/8/2022)

Poor wifi, must dedicate little time left to uploading photos. Underside of bridge at Stalingrad. Feel trapped by spikes.

Building reminds me of temple in Yangon, built in brutalist style.

Fall rains are back. Staying in Nanterre, came to city for business.

-Thura Nu

(22/1/2023)

It’s been a while since I was able to to really update this website on what has happened to me. After leaving the overflow zone outside of the Maison, I was a wanderer for a bit until I found a shanty town in Nanterre where I could set myself down. While there I couldn’t take my camera out of its bag, so my only options for livelihood were peddling cigarettes down at Porte de Clingincourt and trading with other migrants at the camp under the Stalingrad metro bridge. After a while Nanterre became too far away for me to manage coming into the city regularly, especially after having several close calls with the RATP police who threatened to turn me over to the immigrations office if I didn’t pay my ticket. Since I figured it would be easier to move around within the city, I made my way down to Rue Raymond in the XIVème. It is essentially a long corridor of tents behind a corner in an unsuspecting neighborhood. Above us is a small wood, though in truth its just some trees up on a dirty hill covered in small trees that opens onto a semi-abandoned railway station and a set of tracks that lead nowhere in particular. For a time I lived in a tent in the middle of an avenue, and each morning I would wake up before the cars really started to get heavy, or else I would suffer stares from the commuters as they went to their jobs at different places around the city as I was getting out of bed and enjoying the morning summer sun. As the months got colder, I realized that it would not be the smartest idea to stay in the middle of a road that might get icy, especially with record temperatures being set every year nowadays, so I moved over to the camps at La Redoute de Gravelle in the expansive Bois de Vincennes. Though out of the way, here I was in a large community of migrants, and I could get warmth from the generator that some of them had managed to rig up between their tents. In December, I took these photos up on the avenue of Pigalle. I noticed the pigeons would take off and fly away from a building, and then they seemed to be back once again after a moment or two. Soon I realized that they were passing back and forth between the buildings along the avenue. From one to the other, from the north to the south, they would switch places, back and forth, getting up and moving in droves, seemingly only when enough of them had decided that it was the right moment. Sometimes there was a lone pigeon, whom on his own would set course for another roost, only to soon be joined by the others.

It all reminded me of how I had been moving around, from camp to camp, destitute, seemingly only waiting for my 18 months to expire, running out the clock until the sun set and I could sleep in one roost again. Sometimes I was one of the flock, sometimes I was the lone pigeon. But then, as I was waiting to get a photo of the birds jumping off of their roost to fly down the avenue towards the other, waiting patiently with my camera in hand, ready to capture them at a moment’s notice, I remembered the police back at Jardins d’Éole, and how they would watch like hawks from the edge of the fence as we went about our day. I felt that same tension that I had felt back then too, staring at the officers body armor as they lined up against the gate.

The tension of guessing who would make the first move, the tension of waiting. I was also reminded of the big CRS vans that patrol the city with their sirens blasting, seemingly watching us migrants from all corners. Since it is January now, it has been 18 months since my initial arrival in France, and so I am going to go to OFII again to see if they can help me with my application.

-Thura Nu

(25/1/2023)

OFII has managed to find me a spot at the Maison des Réfugiés again, and they have a date set for me with an immigration officer who is willing to look over my asylum application case. The date is set for the 21st of February, but I need to use their computers to establish the office in which I will have the appointment through their official website, and the service is seemingly down. But for the moment, I am able to see hope again in my future. In the meantime, I have been looking at news articles from Myanmar to see if I can get word of what might have happened to my family. So far all I can see is that the resistance has hidden itself, and that the Junta has been cracking down brutally on many villages. I fear that if they were not able to escape they may be dead. I remember seeing a photo in Le Figaro of soldiers from Myanmar, and one of them looked a lot like my younger brother, but there was no way for me to confirm it at the time, as he was far away and in the background. But if so, that would have put at least him, but potentially more of my family, in Loikaw to the north. I will keep searching while I wait.

-Thura Nu

(21/2/2023)

I am still in the Maison, but my appointment was scheduled for June, after having to wait for weeks on end for the website to finally be repaired, there had seemingly been a huge influx of migrants from Syria and another wave from Ukraine, so my priority has been pushed to the bottom of the pile. However, I do have a date established, so in June I will go in for my appointment and maybe I can finally get a proper standing in this country. Still, news of my family is seemingly impossible to find, and I have only been able to concur that the rebel forces in Loikaw were driven out. I hope my brother was not there when they came, hardly anybody survived.

-Thura Nu

(17/5/2023)

I am starting to fear that my family was not able to escape before the iron curtain came down around the country. My sister had contacts in Singapore, and I reached out to some of them via email, but I severely doubt that I will get a response. Nobody has posted to social media in nearly two years, and the last posts seem to just be about praying that this will all be over soon. I think when I am finally given asylum status, if through that they allow me to gain some sort of working visa, I will take time to go back to “Indochine” and investigate what might have happened to my family in person.

-Thura Nu

(17/6/2023)

My appointment came and went. Once again, they refused my status. I am at a loss for words, truly. I thought that Europe was the place that had invented “humanitarianism,” that being a policy of helping other humans, simply because they are human; that perhaps here in Europe there was some kind of advancement made beyond the simplistic nationalism that had become so rampant in my home, but now that I am here I see it is no different. “Humanitarianism” is just a mask, a way for one nation to say to the world “we are good! we accept the needy!” and to get brownie points for it, as it where; but in all actuality, they have just taken the process of being humane and kind to those around you and institutionalized it, sucking the life out of the one thing that sought to make the process human in the first place: the instinct to help. While European scholars sit there and think about what the proper ways to handle the morality of helping others are, and how to properly and succinctly define it for their next paper, there are real people out there who need their help. What is the mission of a humanitarian if not to help those in need? Apparently, it is decide who to help and who not to help. Who to accept and who to refuse. A young Ukrainian boy I met several months ago recently told me that they have accepted his asylum status in France, and so he is continuing on with his original plan of finding work in Bordeaux on a wine vineyard. He left Ukraine in 2020, two years before the war broke out. I left between the dates of the coup-d’état and the beginning of the war, and yet my story is placed into an uncomfortable limbo of uncertainty. Tomorrow I am going to leave the Maison again, probably for the last time. I’ll be back in the camps, there is nowhere else that wants to take me. Ultimately they were unable to process my status because of my initial mistake of staying in that Jardins d’Éole camp on the eve of the police raid. My fingerprint being in the system seems to have been enough to knock me out of consideration. I feel like I am being funneled back into the shanty town, as if my position as a low-life in this city has been forced upon me, despite my French education and my status as a graduate of an international school of photography. None of that matters though when the only record of your name is attached to a fingerprint they took of you after they found you living in a crack hotspot. I hear the Jardins are now a place where migrants can get food in the morning. Maybe I will go by there some day.

-Thura Nu

(8/4/2024)

Today I find myself on a bus, headed to Alsace. This is the first time I have had a stable connection to wifi since my last days at the Maison nearly a year ago, and so I am going to try to fill in the gap. After being tossed from the Maison again after my asylum status was refused, I had to find a way to evade the police, who as it turns out had been planning to send me “back to where I had come from” since they first set eyes on me. I left XVIIIème and made my way to the Lycée Hôtelier in the XIXème, an old abandoned Lycée that had become a kind of haven for migrants who needed a home.

It had fallen into disrepair, and to prevent chunks of the hundred-year-old façade from falling onto passersby the local government of the arrondissement had covered it with netting. This also had the convenient effect of shielding the inside from prying eyes, so it was a welcome change for the migrants who had decided to call it home. I managed to stay there through the summer; the drafty halls of the old school were perfect cover for the record-breaking heat of that august, and I would spend my time between there and the streets of the quartier of Gare d’Austerlitz to the south. I couldn’t stop staring up at the lights in the metro, feeling lost.

There were about a hundred markets between there and the Lycée, and despite my disheveled appearance I was still able to strike up conversations with several of the stall owners. In December I returned to the Marché aux Pouces in Saint-Ouen to search for the camera seller and give him my deepest gratitude, but he was nowhere to be found. This camera has saved my life. Though I don’t use it much, I have ended up taking photos of the things around me in this life when I feel the most lost, and putting them up on this website is in some ways able to repair my hurt, as if to heal the wounds into scars to be gazed at. Something to be appreciated, seen, respected, venerated. Something with a story behind it. At the turn of the Gregorian year, from 2023 to 2024, I left the Lycée and made it to a new encampment that had been gaining traction, set up at the base of the Stade de France in the north area of Seine Saint-Denis. This was the place where I met a worker from OFII, Ophélie, who had heard of my case and was willing to try and get me back into the asylum process again, seeing as how I had been implicated in the whole Éole mess by sheer coincidence. But, she told me that if I was to do it right, I would have to be patient and wait for the right time to make the case with the courts again. Maybe May or June, she said, or maybe after the Olympics has passed. But ultimately that waiting is what has put me on this bus. Yesterday, a group of police came and raided our camp, not unlike the ones in Jardins d’Éole, only this time with less guns and batons and more blankets. They said they were there to help us, that they were moving us to a facility that could process our requests for asylum properly, and that we would be shipped off to Alsace. Just a week ago I saw a man in an Olympic Games vest and hat patrolling the area of our camp, measuring the site with his eyes. I think that if the police had truly cared for us they would have come and gotten us out of there before the winter hit and we lost ten people to the cold rain and frosts. This was nothing more than a routine clearing out of we the migrants who are seen as a pest problem, just like the rats. Sitting on this bus, I feel as though I have gone nowhere since that bus dropped me off in Dresden, or even in Darjeeling. It’s just been the same motion: from one place to the next, disregarded by each group of people that I have come to seeking help. The only ones that seemed amicable to my cause where the ones who acted as traffickers and got me to Europe, but once I was here my luck ran out. Thura in Burmese means resilience, bravery. I have always carried it with me, an epithet acting as a sort of charm, helping me through these dark and arduous times I have experienced as a migrant in the past three years. I will continue to persist, and I hope that the next time I update this website it is because I have finally gotten an asylum claim to come through. Maybe it will be in Spain, or the UK, or Italy. I don’t know. I only know that the road that lies ahead seems no shorter than the one that lies behind, and so I must continue on.

-Thura Nu

Details regarding nature of student project, Julian Dixey

This is a creative project created for the purposes of a final assignment in a class taken at the American University of Paris on Migration. This story does not pretend or claim to represent any specific individual, instead attempting to assemble an accurate depiction of the struggle that one might face as an outsider who is stuck in the sometimes endless loop of European humanitarianism in the structure of the asylum application. This story is however just fantasy, and it also does not claim to accurately represent any of the organizations detailed above.

Lastly, It should also be stated, for continuity’s sake, that in the world of Thura Nu, he would have written this all in French, however seeing as my French is not quite up to snuff, I have instead opted to impose some representations of a French speaker into the text (for example writing “XIXème,” to specify an arrondissement in Paris).

-Julian James Dixey, 14 April, 2024.

Sources (MLA 9)

“Accueil, OFII.” Office Français de l’Immigration et de l’Intégration, https://www.ofii.fr/.

“Burmese Names.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Burmese_names.

“Carte Interactive des Migrants à Paris.” France 24, https://graphics.france24.com/carte-migrants-paris/.

Czaja, M., Vogel, O. “JO 2024 : Que Deviennent les Migrants Transférés de Paris Vers l’Alsace ?” France Bleu, https://www.francebleu.fr/infos/societe/jo-2024-que-deviennent-les-migrants-transferes-de-paris-vers-l-alsace-5831196.

“Évacuation d’un Important Campement de Migrants au Pied du Stade de France à Saint-Denis.” Le Monde, 17 Nov. 2020, https://www.lemonde.fr/societe/article/2020/11/17/evacuation-d-un-important-campement-de-migrants-au-pied-du-stade-de-france-a-saint-denis_6060013_3224.html.

Hughes, S., Le Stradic, S. “France Is Busing Homeless Immigrants Out of Paris Before the Olympics.” The New York Times, 11 July 2024, https://www.nytimes.com/2024/07/11/world/europe/france-is-busing-homeless-immigrants-out-of-paris-before-the-olympics.html.

Kobane, Raqqa. “The Kurds Are Creating a State of Their Own in Northern Syria.” The Economist, 23 May 2019, https://www.economist.com/middle-east-and-africa/2019/05/23/the-kurds-are-creating-a-state-of-their-own-in-northern-syria.

“Myanmar Civil War (2021–Present).” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Myanmar_civil_war_(2021%E2%80%93present).

“The Myanmar Calendar.” Frontier Myanmar, https://www.frontiermyanmar.net/en/the-myanmar-calendar/

.

“Thousands of asylum seekers waiting in streets, makeshift camps around Paris.” FRANCE 24 English, Youtube.com, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2htRQwzI5jY.